Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

Is Islam “satanic”?

Personally, I don’t believe Satan, or God, exist, so it’s not a question I give a great deal of time to.

Salman Rushdie gave it some thought. The title of The Satanic Verses comes from an old idea that there may have been parts of the Sura that were false. Specifically, a concession to the polytheism of the pre-Islamic Meccans to whom Muhammad preached: “And see ye not Lat and Ozza, And Manat the third besides? These are exalted Females, And verily their intercession is to be hoped for.”

Muhammad was, the story goes, tricked into saying these lines by Satan. The Angel Gabriel later told Muhammad he had been deceived, and he recanted.

For Thought-For-The-Day types, it’s a nice little “don’t believe everything you read” lesson. For literary types, it may even be seen as an interesting early example of an unreliable narrator. Muhammad trusted the angel to tell him the truth: but at that moment, the angel was not who he seemed.

I sincerely doubt Northern Ireland’s Pastor James McConnell has much truck with the idea of unreliable narration. Or even fiction, for that matter. McConnell is the type of person who believes that if someone is going to go to the trouble of writing a thing down in a book, then that thing should be true.

A book? No. The Book. There is one book for the pastor. It’s called the Bible, and it’s got everything you need. You might read other books, but they’ll be books about the Book. Books explaining in great detail just how great the Book is. What there are not, cannot be, are other the Books.

So the Bible can be true, or the Quran can be true: but they can’t both be true. And if the Quran is false, but Islam claims it is true, then Islam must be wicked. Satanic, even.

In May last year, Pastor McConnell, like many of his ilk, was very exercised by the story of Meriam Yehya Ibrahim, who had reputedly been sentenced to death in Sudan after converting from Islam to Christianity. Here was further proof, septuagenarian McConnell preached to the congregation at Whitewell Metropolitan Tabernacle, that “Islam is heathen, Islam is satanic, Islam is a doctrine spawned in hell.” There may be good Muslims in the UK, he said, but he didn’t trust them. Enoch Powell was right, McConnell said, to predict “rivers of blood”.

McConnell seemed to know this was going to get him in trouble. “The time will come in this land and in this nation,” he preambled, “to say such things will be an offence to the law.”

Turns out, the pastor was half-right at least in this much. Last week, Northern Irish prosecutors announced that McConnell would face prosecution for his sermon. For inciting religious hatred? No, too obvious. McConnell, now retired and said to be in declining health, will be prosecuted under Section 127 of the Communications Act.

Section 127 is, free-speech nerds may recall, the piece of legislation that pertains to the sending “by means of a public electronic communications network a message or other matter that is grossly offensive or of an indecent, obscene or menacing character”.

It’s the one that led to the Paul Chambers “Twitter Joke Trial” case, one of the great rallying points of online free speech in recent years. In January 2010 Chambers joked online that he would blow up Doncaster Robin Hood airport if his flight to Belfast (always Belfast!) to meet his girlfriend was cancelled. He was convicted, even though every single person involved in the case acknowledged that he had been joking, including the airport security, who did not for one second treat the tweet seriously, even as a hoax.

Chambers was convicted. Eventually, in June 2012, the conviction was quashed. Questions were raised about why then-Director of Public Prosecutions Keir Starmer had persisted in pursuing the case. For his part, Starmer launched a consultation to draft guidelines on when the Communications Act provisions should and should not be used (this writer took part in the meetings and submitted written evidence).

During that process, Starmer was fond of pointing out (correctly) that the Communications Act had been designed to protect telephone operators from heavy breathers. It had nothing to do with stupid jokes on the internet.

And it certainly had nothing at all to do with the online streaming of sermons by fundamentalist preachers.

Let there be no doubt: the prosecution of James McConnell under the Communications Act is a disgrace and a travesty. It is the action of a prosecution service more interested in appearing to be liberal than upholding justice and rights. If McConnell is suspected of being guilty of incitement, then prosecute him under that law. But the deployment of the catch-all Communications Act, in a situation it was very obviously not designed for, suggests prosecutors were not confident of that case and have instead reached for the vaguest charge possible.

When one combines this latest prosecution with the recent “gay cake” case, in which a Christian bakery in County Antrim was fined for refusing to decorate a cake with a pro-equal marriage message, it’s hard not to think the people of Protestant Ulster may, on this occasion, have some real fuel for the siege mentality that’s kept them going for so very long. It feels as if an attempt is being made to force liberalisation on Christians through the courts. It’s hard to imagine any outcome besides resentment, and Lord knows the “wee province” has enough of that already.

This column was published on 25 June 2015 at indexoncensorship.org

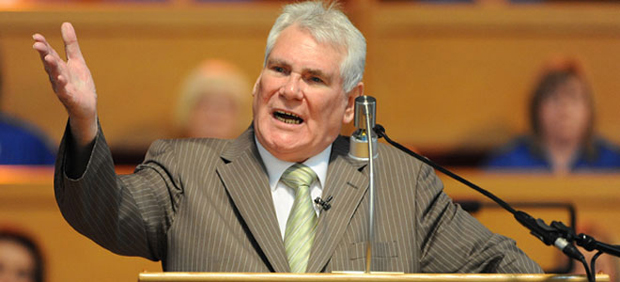

Pastor James McConnell

Belfast’s Whitewell Metropolitan Tabernacle is one of those things that makes a soft Southern Irish atheist Catholic like me think I’ll never truly understand Northern Ireland.

Every week, Ulster Christians flock from across the province to the 3,000-seater auditorium, there to hear Pastor James McConnell preach his Christian message. Not the Christian message of the BBC’s Thought For The Day, however; you may hear Beatitudes at Whitewell, but it’s not a place for platitudes. This is the real deal, fire and brimstone; damnation and salvation. If you’re not going to Whitewell, you’re going to Hell.

It is a comforting message, and actually, a very modern one. Think of how many politicians these days talk about how they work for hard-working-families-that-play-by-the-rules. Hardline evangelical Christianity is the epitome of that idea. We don’t refer to the “Protestant Work Ethic” for nothing.

But what we tend to forget when discussing hardliners from the outside is that there is a strong apocalyptic element in orthodox monotheistic religion. This is particularly true of Christianity. The closer to the core you get, the more you find Jesus’s teachings are essentially about the end of the world, not some vague being-nice-to-one-another schtick.

For some time, Christians have fretted over Matthew 24, in which Jesus apparently tells of the signs of his second coming, that is, to, say, the end of the world. What worries them particularly is Matthew 24:34: “Verily I say unto you, This generation shall not pass, till all these things be fulfilled.”

Does this mean Jesus was telling his apostles that the world would end in their lifetime? CS Lewis, in his work The World’s Last Night, seemed to believe so, and went so far as to call the Messiah’s assertion “embarrassing”. Lewis wrote:

“‘Say what you like,’ we shall be told, ‘the apocalyptic beliefs of the first Christians have been proved to be false. It is clear from the New Testament that they all expected the Second Coming in their own lifetime. And, worse still, they had a reason, and one which you will find very embarrassing. Their Master had told them so. He shared, and indeed created, their delusion. He said in so many words, ‘This generation shall not pass till all these things be done.’ And he was wrong. He clearly knew no more about the end of the world than anyone else.”

“It is certainly the most embarrassing verse in the Bible. Yet how teasing, also, that within fourteen words of it should come the statement ‘But of that day and that hour knoweth no man, no, not the angels which are in heaven, neither the Son, but the Father.’ The one exhibition of error and the one confession of ignorance grow side by side.”

Lewis, though himself a Northern Irish Protestant, was clearly not of the same cloth as Pastor McConnnell, Ian Paisley, and the other preachers of their ilk. Orwell disdained Lewis for his efforts to “persuade the suspicious reader, or listener, that one can be a Christian and a ‘jolly good chap’ at the same time.” The booming pastors of Northern Ireland, and other Christian strongholds such as the US’s Bible Belt, are very firmly convinced that the end is imminent. And thus, they do not have time to be “jolly nice chaps”. There are souls to be saved, right now.

It’s this attitude that has got Pastor McConnell into trouble in the past week. Recently, at Whitewell, inspired by the story of Meriam Yehya Ibrahim, a Sudanese woman reportedly sentenced to death for converting to Christianity, McConnell told the thousands assembled at his temple that “”Islam is heathen, Islam is Satanic, Islam is a doctrine spawned in Hell.”

In an interview with the BBC’s Stephen Nolan, McConnell refused to back down, claiming that all Muslims had a duty to impose Sharia law on the world, and suggesting they were all merely waiting for a signal to go to Holy War. A subtle examination of modern Islamist and jihadist politics this was not.

The PSNI is now investigating McConnell for hate speech. Northern Ireland’s politcians have been quick to comment. First Minister Peter Robinson backed McConnell, first saying that the preacher did not have an ounce of hate in his body, and then managing to make the situation worse by saying he would not trust Muslims on spiritual issues, but would trust a Muslim to “go down the shops for him”.

Insensitive and patronising that may be, but Robinson also touched on something more relevant to this publication when he said that Christian preachers had a responsibility to speak out on “false doctrines”.

The issue raised is this: if we genuinely believe something to be untrue, no matter how misguided we may be, do we not have a right to challenge it in robust terms? In politics we often bemoan the fact that leaders will not call things as they, or we, see them: indeed, Tony Blair, the bete noire of pretty much every political faction in Britain (a bete noire who oddly managed to win three election) has found grudging praise from across the spectrum this week for suggesting that rather than “listening to” or “understanding” the xenophobic United Kingdom Independence Party, politicians should tackle their arguments head on.

But in religion, we tend to hope that no one will upset anyone too much, in spite of the fact that, for true believers, theological issues are far more important than taxation or anything else.

When Blair’s government proposed (and eventually passed) a law against incitement to religious hatred in Britain, the opposition came from a coalition of secularists and some evangelical Christians, both groups realising, for different reasons, that being able to call an ideology false or untrue – and in the process criticise and question its adherents – was a fundamental right. The trade off in that is acknowledging others’ right to question your truths, something I suspect, judging by the recent controversy in Northern Ireland over a satirical revue based on the Bible, Pastor McConnell and his supporters may not quite excel at.

This article was originally posted on May 29, 2014 at indexoncensorship.org