11 Dec 2010 | Uncategorized

Julian Assange’s lawyers are saying that a US indictment is imminent. But what crime would he actually be guilty of? The Congressional Research Service pointed out earlier this week, in a fascinating document published on Steven Aftergood’s always enlightening Secrecy News, just how difficult it would be to nail him.

Past prosecutions have been almost entirely of individuals who have access to classified information and leak it to foreign agents (not to the press for publication).

And there are no cases of publishers being prosecuted. There have been calls for Assange’s prosecution under the Espionage Act, which covers the leaking of documents relating to the US’s national defence. Yet although some of the diplomatic cables would fit that category, it is not illegal to disclose the information unless you are a government employee.

The US government would have to prove that Assange was disseminating documents with intent to harm the US’s national security — and here, once again, the act of publishing the documents is unlikely to be an offence and would be protected by the First Amendment.

The Supreme Court has been wary in the past of using the Espionage Act to punish whistleblowers “who reveal information that poses more of a danger of embarrassing public officials than of endangering national security”.

Extradition would also be immensely complex, not least because it is not allowed when the offence is political.

10 Dec 2010 | Americas, Mexico

As in every country affected by Wikileaks, Mexico is trying to figure out what to learn from the released cables that undress what U.S. officials think of this country and its politicians.

In the released documents US Ambassador Carlos Pascual, and other US officials, openly discuss their doubts about the effectiveness of Mexican security institutions.

But what has sent people into a spin are revelations that US agencies were the ones that had the intelligence that led Mexican Navy units to ambush and kill a powerful drug trafficker in December last year. One cable also reveals that it was US forces that hand-picked the Mexican Navy to carry out this and other attacks against wanted drug traffickers.

But for those who do not get offended by the fact that their next door neighbour is prying into internal affairs, the cables have contributed to provide the common citizen with more information on how their government is carrying on with the drug war.

The progressive newspaper La Jornada published a very thoughtful editorial last Sunday which argued that the cables confirm many truths often denied by the government of Felipe Calderon in its battle against drug traffickers. One cable revealed that there was serious in-fighting between the two government organs that oversee justice and police work. The head of the Public Security Ministry, Genaro Garcia Luna and former attorney general Eduardo Medina Mora, went at each other´s throat for most of the first half of Calderon’s presidential term between 2007 and 2009. The revelations in the cable feed into Mexico’s penchant for conspiracy theories. For the last three years rumours printed in columns by prestigious journalists talked about the fight between the two top government officials over operations, intelligence and the President’s ear, but the rumours were never clarified by the government and were always denied.

Today with the Wikileaks revelations, the public that has taken the time to read the stories on the revelations is better informed, but the government has lost face as it enters its last two years in office and confronts its worst public image. According to a recent poll by Consulta Mitofsky, three of every four Mexicans queried believes they live in a worse situation now than a year ago. The president closes his fourth year in office with a dismal approval rate of 54 percent.

Wikileaks here helped keep the electorate informed with old news, but the impact is still the same–more transparency.

The same is occurring in Bogota, Colombia, in an internal scandal in which the security apparatus of the former President Alvaro Uribe allegedly organised phone tapping of leading politicians, jurists and journalists.

The information was first revealed in documents leaked to the prestigious magazine Semana last year. But Wikileaks tops those past revelations. In one cable, it is none other than General Oscar Naranjo, Colombia’s National Police Director and a well respected official around the world, telling the US Ambassador that the phone taps were ordered by the private secretary of President Uribe, Bernardo Moreno and the presidential advisor, Jose Obdulio Gaviria. Both officials were often thought to be behind the dubious activities that marked the government of President Uribe’s last year in office.

But again, the fact that the US Embassy and one of Colombia’s top police authorities reveal those charges as strong possibilities gives Colombian citizens more information than they had directly from their government officials.

Thus the contributions of Wikileaks are opening a window of transparency in societies where common citizens are not provided with the necessary information to make informed decisions about how their governments are operating.

8 Dec 2010 | News

Financial journalist Nick Kochan explains that whoever is masterminding the economic suffocation of Wikileaks is using the same tactics as those who target terrorist groups

(more…)

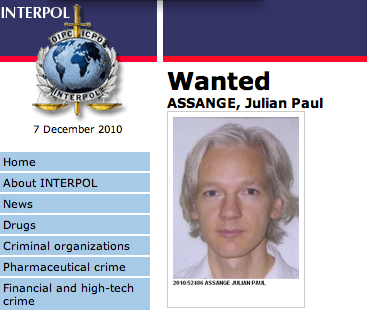

7 Dec 2010 | News

A London court today refused to grant bail to Wikileaks’ founder Julian Assange. Assange is facing extradition to Sweden on sexual assault charges including one count of unlawful coercion, two counts of sexual molestation and one count of rape.

(more…)