14 Sep 2016 | News, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

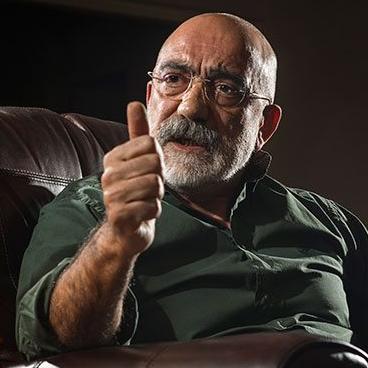

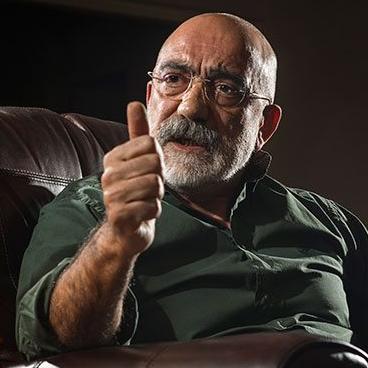

Jailed Turkish journalist Ahmet Altan.

If made out of the right stuff a journalist is a tough nut. Some of us are, you may say, born that way. Our profession lives in our cells. We are compelled to do what our DNA instructs us to do.

Yet, these days, I can’t help waking up each morning in a state of gloom.

Never before have we, Turkey’s journalists, been subjected to such multi-frontal cruelty. Each and every one of us have at least one — usually more — serious issue to wrestle with. Many have already faced unemployment. According to Turkey’s journalist unions, more than 2,300 media professionals have been forced to down pens since the coup attempt. The silenced face a dark destiny: they will never be rehired by a media under the Erdogan yoke.

More than 120 of my colleagues are in indefinite detention – and that number does not include 19 already sentenced to prison. The latest to be added to the list are the novelist and former editor of daily Taraf, the renowned journalist Ahmet Altan and his brother, Mehmet Altan, a commentator and scholar.

The grim pattern of arrests comes with a note attached: “To be continued…”

Nobel Laureate Orhan Pamuk recently and eloquently summed up what Turkey is becoming: “Everybody, who even just a little, criticises the government is now being locked in jail with a pretext, accompanied by feelings of grudge and intimidation, rather than applying law. There is no more freedom of opinion in Turkey!”

Some of those who are still free, either at home or abroad, may consider themselves lucky – or at least be perceived as such. But the reality is that each and every one of us faces immense hardship.

Being forced into an exile, as I have been, is not an easy existence. Many like me have an arrest warrant hanging over their heads. Others are simply anxious or unwilling to return home.

Pressured by financial strains, a journalist in exile bears the burden of the country they have been torn from while remaining glued to the agony of others.

But there is more. Last week I offered one of my news analyses to a tiny, independent daily — one of the very few remaining in Turkey. Waiving any fee, I asked the editor — who is a tough nut — to consider publishing it. Soon, the text was filed and the initial response was: “This one is great, we will run it.”

Then came a telephone call. Because the editor and I have a friendly relationship, he was open when he told me this: “As we were about to go online with it, one editor suggested we ask our lawyer. I thought he was right in feeling uneasy because everything these days is extraordinary. Then, the lawyer strongly advised against it. Why, we asked. He said that since Mr Baydar has an arrest warrant, publishing a text with his byline or signature would, according to the decrees issued under emergency rule, give the authorities to the right to raid the newspaper, or simply to shut it down. Just like that. Tell Mr Baydar this, I am sure he will understand.”

I did understand. No sane person would want to bear the responsibility for causing the newspaper’s employees to be rendered jobless, to be sent out to starvation.

I have since published piece elsewhere.

This incident is but one in a chain, hidden in Turkey’s relative freedom. It’s a cunning and brutal system of censorship that aims to sever the ties between Turkey’s cursed journalists and their readership. It is a deliberate construction of a wall between us and the public. It is putting us in a cage even if we are breathing freedom elsewhere.

It’s enough to make George Orwell turn in his grave.

But there is some consolation. Thankfully we, the censored among Turkey’s journalists, have space to write about the truth, make comments and offer analysis in spaces like Index on Censorship. Thankfully, we have the internet, which is everybody’s open property, even if the sense of defeat when you awake some mornings leaves you convulsing in the gloom.

You know you have to chase it away and get on with what you know best: to inform, to exchange views, offer independent opinion, promote diversity, and hope that one day it will contribute to democracy.

More Turkey Uncensored

Can Dündar: “We have your wife. Come back or she’s gone”

Turkey: Losing the rule of law

Yavuz Baydar: As academic freedom recedes, intellectuals begin an exodus from Turkey

30 Aug 2016 | Europe and Central Asia, Mapping Media Freedom, mobile, News, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

Award-winning writer, human rights activist and columnist Aslı Erdoğan

“When I understood that I was to be detained by a directive given from the top, my fear vanished,” novelist and journalist Aslı Erdoğan, who has been detained since 16 August, told the daily Cumhuriyet through her lawyer. “At that very moment, I realised that I had committed no crime.”

While her state of mind may have improved, her physical well-being is in jeopardy. A diabetic, she also suffers from asthama and chronic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

“I have not been given my medication in the past five days,” Erdoğan, who is being held in solitary confinement, added on 24 August. “I have a special diet but I can only eat yogurt here. I have not been outside of my cell. They are trying to leave permanent damage on my body. If I did not resist, I could not put up with these conditions.”

An internationally known novelist, columnist and member of the advisory board of the now shuttered pro-Kurdish Özgür Gündem daily Erdoğan was accused membership of a terrorist organisation, as well as spreading terrorist propaganda and incitement to violence.

According to the Platform for Independent Journalism, Erdoğan is one of at least 100 journalists held in Turkish prisons. This number – which will rise further – makes Turkey the top jailer of journalists in the world.

Each day brings new drama. Erdoğan’s case is just one of the many recent examples of the suffering inflicted on Turkey. It is clear that the botched coup on 15 July did not lead to a new dawn, despite the rhetoric on “democracy’s victory”.

Turkey faces the same question it did before the 15 July: What will become of our beloved country? Like the phrase “feast of democracy” – which has been adopted by the pro-AKP media mouthpieces – it has been repeated so often that it habecome empty rhetoric.

Such false cries only serve the ruling AKP’s interests. Even abroad there are increased calls that we should support the government despite the directionless politics in Turkey and the state of emergency.

In a recent article for Project Syndicate entitled Taking Turkey Seriously, former Swedish Foreign Minister Carl Bildt wrote: “The West’s attitude toward Turkey matters. Western diplomats should escalate engagement with Turkey to ensure an outcome that reflects democratic values and is favorable to Western and Turkish interests alike.”

Lale Kemal took Turkey seriously. As one of the country’s top expert journalists on military-civilian relations, Kemal stood up for the truth, barely making a living as no mogul-owned media outlet would publish her honest journalism. She headed the Ankara bureau of independent daily Taraf, now shut down because of the emergency decree. She now sits in jail for the absurd accusation that she “aided and abetted” the Gülen movement, an Islamic religious and social movement led by US-based Turkish preacher Fethullah Gülen. President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan refers to the movement as the Fethullahist Terrorist Organisation (FETO) and blames it for orchestrating the failed coup.

But actually, Kemal’s only “crime” was to write for the “wrong” newspapers, Taraf and Today’s Zaman.

Şahin Alpay also took Turkey seriously. As a scholar and political analyst he was a shining light in many democratic projects and one of the leading liberal voices in Turkey.

Three weeks ago, he was detained indefinitely following a police raid at his home. His crime? Aiding and abetting terror, instigating the coup and writing for the Zaman and Today’s Zaman. This last point is now reason enough to deny such a prominent intellectual his freedom.

Access to the digital archives of “dangerous” newspapers – Zaman, Taraf, Nokta etc – is now blocked. This is a systematic deleting of their entire institutional memory. All those news stories, op-ed articles and news analysis pieces are now completely gone.

Basın-İş, a Turkish journalists’ union, stated that 2,308 journalists have lost their jobs since 15 July, and most will probably never to be employed again. Unemployment was their reward for taking Turkey seriously.

Erdoğan, Kemal and Alpay, like many journalists, academics and artists who care for their country, are scapegoats for the erratic policies of those in power.

Even businessmen have fallen victim to the massive witch hunt against “FETO”. Vast amounts of assets belonging to those accused of being Gülen sympathisers have been seized and expropriated by the state. Not long ago these businessmen were hailed as “Anatolian Tigers”, who opened the Turkish market to globalisation.

The seizures will probably draw complaints at the European Court level. They are sadly reminiscent of the expropriations at the end of the Ottoman Empire, which had targeted mainly Christian-owned assets.

What all of these cases have in common isn’t the acrimony that pollute daily politics in Turkey. It is the total sense of loss for the rule of law, made worse by post-coup developments.

A version of this article originally appeared on Suddeutsche Zeitung. It is posted here with the permission of the author.

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

11 Aug 2016 | Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

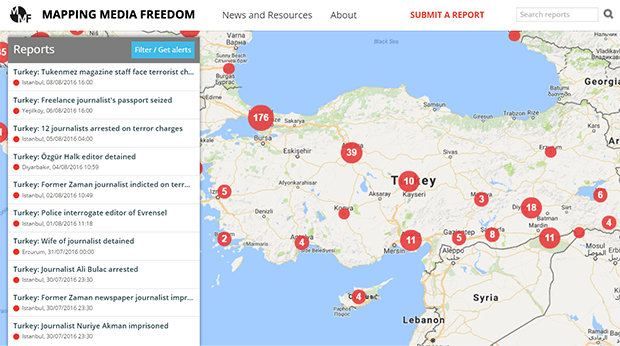

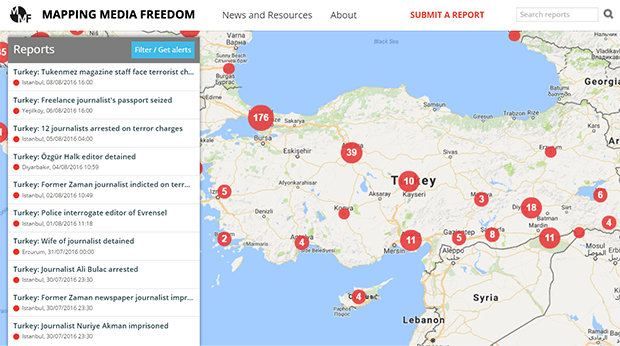

The number of threats to media freedom in Turkey have surged since the failed coup on 15 July.

One of the most vital duties of a journalist — in any democracy — is to report on the day-to-day operations of a country’s parliament. Journalism schools devote much time to teaching the deciphering budgets and legal language, and how to report fairly on political divides and debates.

I recalled these studies when I read an email Wednesday morning from an Ankara-based colleague. I smiled bitterly. The message included a link to an article published in the Gazete Duvar, which informed that 200 journalists had been barred from entering the home of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey. Security controls at the two entrances of the failed-coup-damaged building had been intensified and journalists were checked against a list as they tried to enter.

The reason for the bans? Most of those who were blocked worked for shuttered or seized outlets alleged to be affiliated with the Gülenist movement.

Parliament, though severely damaged by bombing during the night of the coup attempt, is still open. For any professional colleague, these sanctions mean only one thing: journalism is now at the absolute mercy of the authorities who will define its limits and content.

Many pro-government journalists do not think the increasingly severe controls are alarming. “It is democracy that matters,” they argue on the social media. “Only the accomplices of the putschists in the media will be affected, not the rest.”

If only that were true. Reality proves the opposite. Along with the closures of more than 100 media outlets, a wide-scale clampdown on Kurdish and leftist media is underway. Outlets deemed too critical of government policies have come under post-coup pressure.

Late Tuesday, pro-Kurdish IMC TV reported that the official twitter accounts of three major pro-Kurdish news sources — the daily newspaper Özgür Gündem and news agencies DIHA and ANF — were banned. Some Kurdish colleagues interpret the sanctions as part of an upcoming security operation in the southeastern provinces of Diyarbakır and Şırnak.

What I see is a new pattern: in the past three-to-four days, many Twitter accounts of critical outlets and individual journalists have been silenced. An “agreement” appears to have been reached between Ankara and Twitter, but no explanation has yet been given.

For days now, many people have been kept wondering about the case of Hacer Korucu. Her husband, Bülent Korucu, former chief editor of weekly Aksiyon and daily Yarına Bakış, is sought by police after an arrest order issued on him about “aiding and abetting terror organisation”, among other accusations. She was arrested nine days ago as police had told the family that “she would be kept until the husband shows up”.

The Platform for Independent Journalism provided more insight on Hacer Korucu’s detention and subsequent arrest. The motive? She had taken part in the activities of the schools affiliated with Gülen Movement and attended the Turkish Language Olympiade.

Hacer Korucu’s case, without a doubt, shows how arbitrary law enforcement has become in Turkey. As a result no citizen can feel safe any longer.

“She is a mother of five,” was the outcry of Rebecca Harms, German MEP. “A crime to be married to a journalist?”

How do we now expect an honest Turkish or Kurdish journalist to answer this question? By any measure of decency, the snapshot of Turkey in the post-putsch days leaves little suspicion: emergency rule gives a free reign to authorities who feel empowered to block journalists from covering the epicenter of any democratic activity — parliament — and let relatives of journalists suffer.

Meanwhile, we are told on a daily basis that democracy was saved from catastrophe on that dreadful July evening and it needs to be cherished.

But, like this? How?

A version of this article originally appeared on Suddeutsche Zeitung. It is posted here with the permission of the author.

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.

10 Aug 2016 | Academic Freedom, Campaigns -- Featured, Europe and Central Asia, mobile, News, Turkey, Turkey Uncensored

The stream may be small right now, a trickle, but it is unmistakable. Turkey’s academics and secular elite are quietly and slowly making their way for the exits.

Some months ago, in the age before Turkey’s post-coup crushing of academia, a respected university lecturer told me she was seeking happiness outside Turkey. She was teaching economics at one of Istanbul’s major universities, but neither her nor her husband, who is also in the financial sector, had a desire to remain in the country any longer. They simply packed up and left for Canada.

The growing unease about the future is now accelerating among the academics and mainly secular elite in the country. This well-educated section of society is feeling the pressure more than any other, and as the instability mounts the urge to join the “brain drain” will only increase.

Some of them, particularly those academics who have been fired and those who now face judicial charges for signing a petition calling for a return to peace negotiations with the Kurdish PKK, no longer see a future for their careers. With the government further empowered by emergency rule decrees, the space for debate and unfettered learning is shrinking.

One of the petition’s signatories, the outspoken sociologist Dr Nil Mutluer, has already moved to a role at the well-respected Humboldt University in Berlin to teach in a programme devoted to scholars at risk.

You only have to look at the numbers to realise why more are likely to follow in the footsteps of those who have already left Turkey. In the days after the failed coup that struck at the country’s imperfect democracy, the government of president Recep Tayyip Erdogan swept 1,577 university deans from their posts. Academics who were travelling abroad were ordered to return to the country, while others were told they could not travel to conferences for the foreseeable future. Some foreign students have even been sent home. The pre-university educational system has been hit particularly hard: the education ministry axed 20,000 employees and 21,000 teachers working at private schools had their teaching licenses revoked.

Anyone with even the whiff of a connection to FETO — the Erdogan administration’s stalking horse for the parallel government supposedly backed by the Gulenist movement — is in the crosshairs. Journalists, professors, poets and independent thinkers who dare question the prevailing narrative dictated by the Justice and Development Party will hear a knock at the door.

It appears that the casualty of the coup will be the ability to debate, interrogate and speak about competing ideas. That’s the heart of academic freedom. The coup and the president’s reaction to it have ripped it from Turkey’s chest.

But it’s not just the academics who are starting to go. The secular elite and people of Kurdish descent that are also likely to vote with their feet.

Signs are, that those who are exposed to, or perceive, pressure, are already doing this. Scandinavian countries have noted an increase in the exodus of the Turkish citizens. Deutsche Welle’s Turkish news site reported that 1719 people sought asylum in Germany in the first half of this year. This number already equals the total of Turkish asylum seekers who registered during the whole of 2015. Not surprisingly, 1510 of applications in 2016 came from Kurds, who are under acute pressure from the government.

The secular (upper) middle class is also showing signs of moving out. The economic daily Dünya reported on Monday that the number of inquiries into purchasing homes abroad grew four-to-five times the pre-coup level. Many real estate agencies, the paper reported, are expanding their staff to meet the demand. Murat Uzun, representing Proje Beyaz firm, told Dünya:

“The demand is growing since July 15 by every day. Emergency rule has also pushed up the trend. These people are trying to buy a life abroad. Ten to twelve people visit our office every day….Many ask about the citizenship issues.”

Adnan Bozbey, of Coldwell Banker, told the paper that people were asking him: “Is Turkey becoming a Middle Eastern country?”

According to Dünya, the USA, Ireland, Portugal, Greece, Malta and Baltic countries are popular among those who want to seek life prospects elsewhere.

In short, the unrest is spreading. Unless the dust settles and the immense political maneuvering about the course Turkey is on reverses, it would be realistic to presume that a significant demographic shift will take place in the near future.

A version of this article originally appeared on Suddeutsche Zeitung. It is posted here with the permission of the author.

Turkey Uncensored is an Index on Censorship project to publish a series of articles from censored Turkish writers, artists and translators.