29 Jun 2016 | Magazine, Volume 45.02 Summer 2016

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

The truth is in danger. Working with reporters and writers around the world, Index continually hears first-hand stories of the pressures of reporting, and of how journalists are too afraid to write or broadcast because of what might happen next.

In 2016 journalists are high-profile targets. They are no longer the gatekeepers to media coverage and the consequences have been terrible. Their security has been stripped away. Factions such as the Taliban and IS have found their own ways to push out their news, creating and publishing their own “stories” on blogs, YouTube and other social media. They no longer have to speak to journalists to tell their stories to a wider public. This has weakened journalists’ “value”, and the need to protect them. In this our 250th issue, we remember the threats writers faced when our magazine was set up in 1972 and hear from our reporters around the world who have some incredible and frightened stories to tell about pressures on them today.

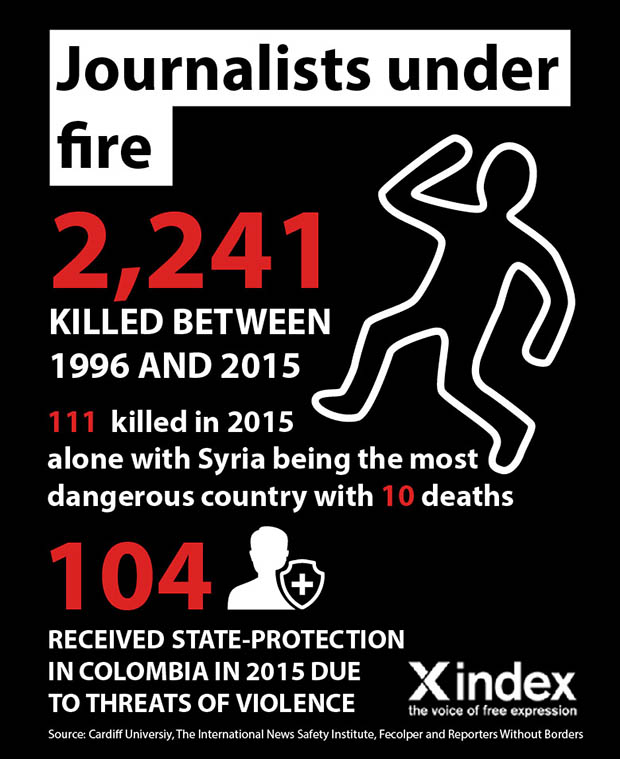

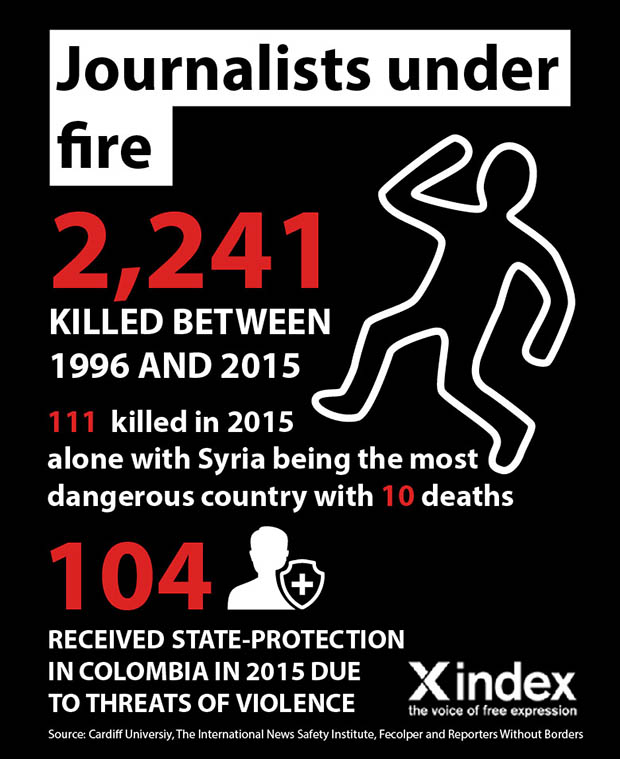

Around 2,241 journalists were killed between 1996 and 2015, according to statistics compiled by Cardiff University and the International News Safety Institute. And in Colombia during 2015 104 journalists were receiving state protection, after being threatened.

In Yemen, considered by the Committee to Protect Journalists to be one of the deadliest countries to report from, only the extremely brave dare to report. And that number is dwindling fast. Our contacts tell us that the pressure on local journalists not to do their job is incredible. Journalists are kidnapped and released at will. Reporters for independent media are monitored. Printed publications have closed down. And most recently 10 journalists were arrested by Houthi militias. In that environment what price the news? The price that many journalists pay is their lives or their freedom. And not just in Yemen.

Syria, Mexico, Colombia, Afghanistan and Iraq, all appear in the top 10 of league tables for danger to journalists. In just the last few weeks National Public Radio’s photojournalist David Gilkey and colleague Zabihullah Tamanna were killed in Afghanistan as they went about their work in collecting information, and researching stories to tell the public what is happening in that war-blasted nation. One of our writers for this issue was a foreign correspondent in Afghanistan in 1990s and remembers how different it was then. Reporters could walk down the street and meet with the Taliban without fearing for their lives. Those days have gone. Christina Lamb, from London’s Sunday Times, tells Index, that it can even be difficult to be seen in a public place now. She was recently asked to move on from a coffee shop because the owners were worried she was drawing attention to the premises just by being there.

Physical violence is not the only way the news is being suppressed. In Eritrea, journalists are being silenced by pressure from one of the most secretive governments in the world. Those that work for state media do so with the knowledge that if they take a step wrong, and write a story that the government doesn’t like, they could be arrested or tortured.

In many countries around the world, journalists have lost their status as observers and now come under direct attack. In the not-too-distant past journalists would be on frontlines, able to report on what was happening, without being directly targeted.

So despite what others have described as “the blizzard of news media” in the world, it is becoming frighteningly difficult to find out what is happening in places where those in power would rather you didn’t know. Governments and armed groups are becoming more sophisticated at manipulating public attitudes, using all the modern conveniences of a connected world. Governments not only try to control journalists, but sometimes do everything to discredit them.

As George Orwell said: “In times of universal deceit, telling the truth is a revolutionary act.” Telling the truth is now being viewed by the powerful as a form of protest and rebellion against their strength.

We are living in a historical moment where leaders and their followers see the freedom to report as something that should be smothered, and asphyxiated, held down until it dies.

What we have seen in Syria is a deliberate stifling of news, making conditions impossibly dangerous for international media to cover, making local news media fear for their lives if they cover stories that make some powerful people uncomfortable. The bravest of the brave carry on against all the odds. But the forces against them are ruthless.

As Simon Cottle, Richard Sambrook and Nick Mosdell write in their upcoming book, Reporting Dangerously: Journalist Killings, Intimidation and Security: “The killing of journalists is clearly not only to shock but also to intimidate. As such it has become an effective way for groups and even governments to reduce scrutiny and accountability, and establish the space to pursue non-democratic means.”

In Turkey we are seeing the systematic crushing of the press by a government which appears to hate anyone who says anything it disagrees with, or reports on issues that it would rather were ignored. Journalists are under pressure, and so is the truth.

As our Turkey contributing editor Kaya Genç reports on page 64, many of Turkey’s most respected news outlets are closing down or being forced out of business. Secrets are no longer being aired and criticism is out of fashion. But mobs attacking newspaper buildings is not. Genç also believes that society is shifting and the public is being persuaded that they must pick sides, and that somehow media that publish stories they disagree with should not have a future.

That is not a future we would wish upon the world.

Order your full-colour print copy of our journalism in danger magazine special here, or take out a digital subscription from anywhere in the world via Exact Editions (just £18* for the year). Each magazine sale helps Index on Censorship fight for free expression worldwide.

*Will be charged at local exchange rate outside the UK.

Magazines are also on sale in bookshops, including at the BFI and MagCulture in London, Home in Manchester, Carlton Books in Glasgow and News from Nowhere in Liverpool as well as on Amazon and iTunes. MagCulture will ship anywhere in the world.

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_custom_heading text=”From the Archives”][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”94291″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228208533353″][vc_custom_heading text=”Afghanistan in 1978-81″ font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228208533353|||”][vc_column_text]April 1982

Anthony Hyman looks at the changing fortunes of Afghan intellectuals over the past four or five years.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”94251″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228208533410″][vc_custom_heading text=”Colombia: a new beginning?” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228208533410|||”][vc_column_text]August 1982

Gabriel García Márquez and others who faced brutal government repression following the 1982 election.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”93979″ img_size=”213×289″ alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/03064228408533703″][vc_custom_heading text=”Repression in Iraq and Syria” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:http%3A%2F%2Fjournals.sagepub.com%2Fdoi%2Fpdf%2F10.1080%2F03064228408533703|||”][vc_column_text]April 1983

An anonymous report from Amnesty point to torture, special courts and hundreds of executions in Iraq and Syria. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Danger in truth: truth in danger” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2F2016%2F05%2Fdanger-in-truth-truth-in-danger%2F|||”][vc_column_text]The summer 2016 issue of Index on Censorship magazine looks at why journalists around the world face increasing threats.

In the issue: articles by journalists Lindsey Hilsum and Jean-Paul Marthoz plus Stephen Grey. Special report on dangerous journalism, China’s most famous political cartoonist and the late Henning Mankell on colonialism in Africa.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_single_image image=”76282″ img_size=”medium” alignment=”center” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2016/05/danger-in-truth-truth-in-danger/”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/3″][vc_custom_heading text=”Subscribe” font_container=”tag:p|font_size:24|text_align:left” link=”url:https%3A%2F%2Fwww.indexoncensorship.org%2Fsubscribe%2F|||”][vc_column_text]In print, online. In your mailbox, on your iPad.

Subscription options from £18 or just £1.49 in the App Store for a digital issue.

Every subscriber helps support Index on Censorship’s projects around the world.

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

15 Apr 2016 | About Index, Awards, Fellowship, Fellowship 2016, News

Words by Alessio Perrone and Sean Gallagher

Photos: Sean Gallagher

“I invite people like this: I just say – you paint now.” That’s how it works with street artist Murad Subay.

His murals grew from the frustration he felt as his homeland, Yemen, descended into chaos and factionalism. Amid the destruction and anger, Subay picked up his brush. With friends, he went out into the streets and began painting in broad daylight. Days passed, then people from the community joined him. All of them driven by their desire for peace amid Yemen’s civil war.

Since 2011 he’s created campaigns to encourage Yemenis to express their outrage at what their country has become. He and his collaborators have coloured walls, named the disappeared and marked ruins.

He always works during the day. It’s always part performance, part collaboration. Thursday 14 April was no different. Only the location had changed.

For his first mural outside Yemen, Subay took his brushes and paint to the corner of Hackney Road and Cremer Street to send a pointed message about the international community’s lack of humanity, especially toward his homeland. Even dogs are better than some of the global institutions and structures.

In London, to receive the 2016 Freedom of Expression Arts Award for his work, which Subay stressed is for Yemen. His acceptance speech was dedicated to the “unknown people who struggle to survive”.

Invited by Jay, the community curator of Art Under the Hood, Subay set up his equipment — with the help of new friends — and began transforming a hoarding into his vision using stencils he had laboured over since arriving on Saturday.

“I’m doing a sun dance.”

“I’m not the type of artist who zones out and thinks this is precious. It’s an ordinary thing for me”

“How long will it take for it to dry?”

“In Sana’a, three minutes!” Then a few seconds later “Here, I don’t know”

“Do you want me to do anything”

“Yes of course. Come here”

“Welcome to the holy state of Hackney, my friend. This is not a borough, not a city, it’s a state.”

“I’ve worked on these stencils from time to time for four days. It’s hard to say how long it takes. Sometimes it takes three, four hours, other times five … Depends on what I do”

“First, try it on the cardboard to see how strong or light it is. Then press in the shape, light, not strong. Keep it at an angle close to the margins, so you can make sure you don’t spray outside the shape. Then perpendicular in the middle. Keep it light, light!”

“Can I have a go?” a young woman asks.

“Yes of course!”

She stops for a moment, hesitant. Then she ends up staying until the very end. And in the end, Subay gives her, Éléa, the stencils when he finishes the mural.

“Do you paint?”

“A bit”

“Not a bit, you have to paint a lot! Painting is beautiful.”

“They have artists in Yemen? First time I hear that!”

“You know how to spray right? Come and learn a bit!”

“When I started out, I was alone, and I did it all in one week. I am slow. In the beginning, I never thought people could join. But then they did. They say: ‘Oh look, the artist!’ And they join”

“These stencils, I made in Yemen. I staged a photo, printed it, then cut it out. That chained man is one of my relatives. He’s a very nice person. He jokes a lot and loves painting. I really like him. We work together a lot, on street art of course but also many different things.”

“It’s all about how the man is suffering. He’s not just Yemen or anybody in particular. It could be any man. The dog is trying to help, and is showing more kindness then the other man. The dog shows that it’s possible to help out, but the other man doesn’t want to do anything.”

18 Mar 2016 | Awards, Fellowship, Fellowship 2016, Middle East and North Africa, Yemen

In 2011, artist Murad Subay took to the streets of Yemen’s capital, Sana’a to protest the country’s dysfunctional economy and institutionalised corruption, and to bring attention to a population besieged by conflict. Choosing street art as his medium of protest, he’s since run five campaigns to promote peace and art, and to discuss sensitive political and social issues in society. Unlike many street artists, all his painting is done in public, during the day, often with passers-by getting involved themselves.

Since 2011, jihadist attacks and sectarian clashes have engulfed Yemen, and in 2015 a civil war began between two factions claiming to constitute the Yemeni government. The exiled Yemeni government, backed by a Saudi-led coalition stood against the Houthi militia, and those loyal to former president Ali Abdullah Saleh and backed by Iran.

In the last seven months the conflict has hit the already unstable country, leading to over 21 million people – 82 percent of the population – needing humanitarian assistance. In addition, a strong Al-Qaeda presence has drawn repeated drone strikes from the United States.

“Yemenis live under catastrophic conditions due to the conflicts, considering that they are already one of the poorest nations in the world,” Subay told Index. “They lack food, water and medicine, and they are in need of urgent humanitarian assistance.” With his art, Subay aims to highlight the situation in which millions of Yemenis find themselves in today.

Murad started his graffiti campaigns with The Walls Remember Their Faces, drawing the faces of Yemeni citizens who had been forcibly disappeared.

“This particular campaign meant so much to me,” he said. “I felt that I got closer to those people every time we painted their faces. Almost every week people came holding the picture of their long disappeared family member, so that we paint it on the walls.”

He then began Colour the Walls of Your Street, claiming back the bombed remains of Yemen’s capital, followed by 12 Hours in 2013. 12 Hours was an hour-by-hour series with each piece depicting one of 12 problems facing Yemen, including weapons proliferation, sectarianism, kidnapping and poverty. The project used social media to call Yemeni citizens to action, painting walls with messages about government and policy across Yemen’s capital.

His latest campaign Ruins was initiated in May 2015, in collaboration with artist Thi Yazen. The project involves them painting on the walls of buildings damaged by the war, to provide a memorial for the thousands of war victims, and to highlight war crimes.

Subay has faced pressure from the authorities, who have covered his work or stopped him from extending his campaigns to other towns. However ordinary Yemenis — including victims’ families — have gotten behind his campaigns by painting alongside Subay, or repainting pieces “scrubbed out” by authorities.

Murad Subay continues to shed light on the human cost of the war, taking his murals to other cities in Yemen, including Aden, Taizz, Ebb and Hodeidah.

16 Dec 2015 | Awards, Events, mobile, Press Releases

A graffiti artist who paints murals in war-torn Yemen, a jailed Bahraini academic and the Ethiopia’s Zone 9 bloggers are among those honoured in this year’s #Index100 list of global free expression heroes.

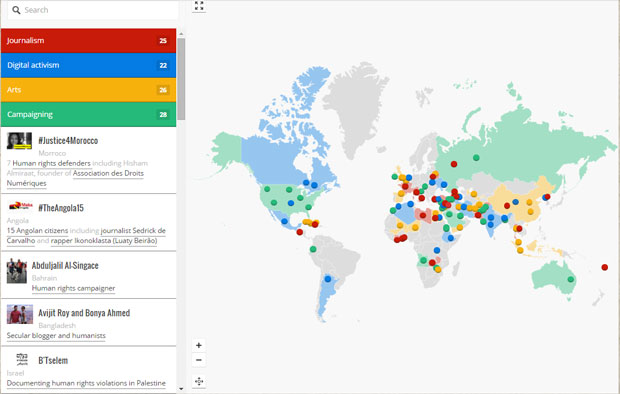

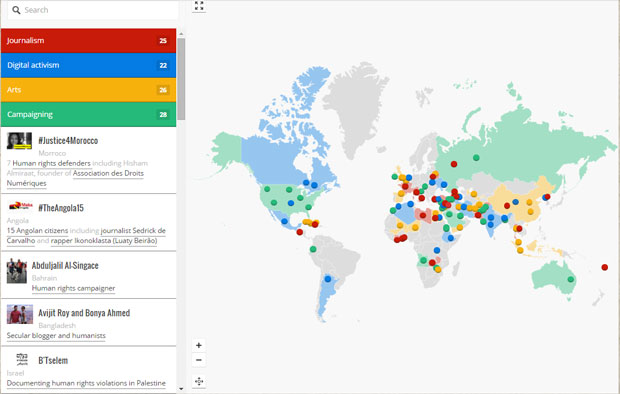

Selected from public nominations from around the world, the #Index100 highlights champions against censorship and those who fight for free expression against the odds in the fields of arts, journalism, activism and technology and whose work had a marked impact in 2015.

Those on the long list include Chinese human rights lawyer Pu Zhiqiang, Angolan journalist Sedrick de Carvalho, website Raqqa is Being Slaughtered Silently and refugee arts venue Good Chance Calais. The #Index100 includes nominees from 53 countries ranging from Azerbaijan to China to El Salvador and Zambia, and who were selected from around 500 public nominations.

“The individuals and organisations listed in the #Index100 demonstrate courage, creativity and determination in tackling threats to censorship in every corner of globe. They are a testament to the universal value of free expression. Without their efforts in the face of huge obstacles, often under violent harassment, the world would be a darker place,” Index on Censorship CEO Jodie Ginsberg said.

Those in the #Index100 form the long list for the Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards to be presented in April. Now in their 16th year, the awards recognise artists, journalists and campaigners who have had a marked impact in tackling censorship, or in defending free expression, in the past year. Previous winners include Nobel Peace Prize winner Malala Yousafzai, Argentina-born conductor Daniel Barenboim and Syrian cartoonist Ali Ferzat.

A shortlist will be announced in January 2016 and winners then selected by an international panel of judges. This year’s judges include Nobel Prize winning author Wole Soyinka, classical pianist James Rhodes and award-winning journalist María Teresa Ronderos. Other judges include Bahraini human rights activist Nabeel Rajab, tech “queen of startups” Bindi Karia and human rights lawyer Kirsty Brimelow QC.

The winners will be announced on 13 April at a gala ceremony at London’s Unicorn Theatre.

The awards are distinctive in attempting to identify individuals whose work might be little acknowledged outside their own communities. Judges place particular emphasis on the impact that the awards and the Index fellowship can have on winners in enhancing their security, magnifying the impact of their work or increasing their sustainability. Winners become Index on Censorship Freedom of Expression Awards Fellows and are given support for the year after their fellowship on one aspect of their work.

“The award ceremony was aired by all community radios in northern Kenya and reached many people. I am happy because it will give women courage to stand up for their rights,” said 2015’s winner of the Index campaigning award, Amran Abdundi, a women’s rights activist working on the treacherous border between Somalia and Kenya.

Each member of the long list is shown on an interactive map on the Index website where people can find out more about their work. This is the first time Index has published the long list for the awards.

For more information on the #Index100, please contact [email protected] or call 0207 260 2665.

![]() SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

SUBSCRIBE NOW[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]