9 Dec 2014 | About Index, Campaigns, Draw the Line, Young Writers / Artists Programme, Youth Board

The second cohort of Index on Censorship’s Youth Advisory Board was announced today. The members will discuss topical freedom of expression events, participate in #IndexDrawtheLine debates and advise Index on youth issues. The new board will sit from December 2014 to May 2015.

Index on Censorship Youth Advisory Board:

Abishek Phadnis

Abishek Phadnis

Abhishek recently completed a Master’s in Diplomatic History from the London School of Economics, and is due to commence doctoral research on an early history of the Indian nuclear weapons programme. As a secularist activist and a fierce campaigner against theocratic censorship in England, he has been honoured by the British National Secular Society for “bravely challenging Islamist groups, his own university (LSE) and Universities UK over important and fundamental issues such as free speech.

Ásta Helgadóttir

Ásta Helgadóttir

Ásta is a deputy member of the Icelandic Parliament for the Icelandic Pirate Party and will take position as an MP in the fall of 2015. Her interest in censorship is both political and academic, mainly focused on the aspects of European legal justifications regarding modern day technological censorship.

Catarina Demony

Catarina Demony

Catarina is the founder of The Voiceless, a media platform about human rights violations, and recently graduated from Kingston University with a Journalism degree. Currently, she works in the communications team at London School of Economics Students’ Union, as well as University of the Arts. Catarina also works closely with Amnesty LDN, part of Amnesty International movement for recent graduates and young professionals.

Jordan Mitchell

Jordan Mitchell

Jordan is a human rights advocate, writer, and Truth About Youth associate working with Ovalhouse Theatre. Based in London, he believes it is imperative for the under-represented to be given a platform, with a particular focus on the role of the media.

Kay Robinson

Kay Robinson

Kay is studying History and Politics at Lancaster University, and is sub-editor for the International Political Forum. A strong supporter of human rights, she believes that free and equal platforms of expression have a crucial role in forming safe, empowered societies.

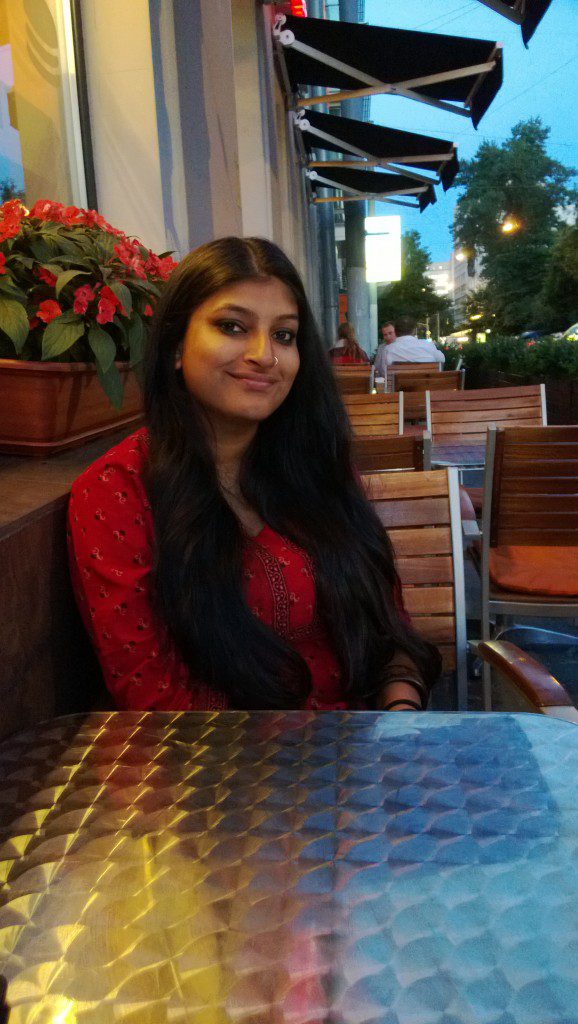

Mahima Singh

Mahima Singh

Mahima works for newslaundry.com, an independent media website in India. Mahima believes that the freedom of expression is one of the core fundamentals of a healthy society . She has been advocating freedom since her college days when she was forced to take down a story she had written because it upset the authority.

Mari Shibata

Mari Shibata

Mari is a freelance newsgatherer for AP Television, a BFI-funded filmmaker and ocassional writer for Vice. Also a Cambridge University graduate in music, she is passionate about issues surrounding free expression in the cultural arts from conflict zones.

Mohanad Moetaz ElHawary

Mohanad Moetaz ElHawary

Mohanad is an Egyptian Engineering major in the Middle East. With the Arab uprisings over the last few years, his passions for freedom of expression and human rights were further consolidated. Mohanad is currently secretary, editor and founding member at a university club called ‘Fikir’ (meaning ‘thought’) that aims to encourage social involvement and responsibility.

The application period for the next youth board will open in May 2015 for the June to November cohort.

What is the youth board?

The youth board is a specially selected group of young people aged 16-25 who will advise and inform Index on Censorship’s work, supporting our ambition to fight for free expression all around the world and ensuring our engagement with issues relevant to tomorrow’s leaders.

Why has Index started a youth board?

Index on Censorship is committed to fighting censorship not only now, but also in future generations, and we want to ensure that the realities and challenges experienced by young people in today’s world are properly reflected in our work.

Index is also aware that there are many who would like to commit some or all of their professional lives to fighting for human rights and the youth board is our way of supporting the broadest range of young people to develop their voice, find paths to freely expressing it and potential future employment in the human rights/media/arts sectors.

What does the youth board do?

Board members meet once a month via Google Hangout to discuss the most pressing freedom of expression issues of the moment and to set a monthly question for our project, Draw the Line. You will be expected to write a minimum of 1 blog post introducing/concluding the question of the month and to help us spread the word about Index.

There is also the opportunity to get involved with events such as debates and workshops for our work with young people and also events such as our annual Index Freedom of Expression Awards and Index magazine launches.

How do people get on the youth board?

Each youth board will sit for a term of 6 months.

Current board members are invited to reapply up to one time.

The board will be selected by Index on Censorship in an open and transparent manner and in accordance with our commitment to promoting diversity.

Why join the Index on Censorship youth board?

You get the chance to be associated with a prestigious media and human rights organisation and have the opportunity to discuss issues you feel strongly about with Index and with other amazing young people (internationally). At each Board meeting we will also give you the chance to speak to someone senior within Index or the media/human rights/arts sectors, helping you to develop your knowledge and extend your personal networks and you’ll be featured on our website.

10 Oct 2014 | Draw the Line, Youth Board

As protests continue to rock many countries, at times leading to use of excessive force including tear gas and rubber bullets by law enforcement officers against protesters, people have openly raised questions on police abuse. This month’s Draw the Line question focused on the excessive use of force during protests and the role police can play in striking the balance between keeping the peace and protecting free speech.

Being a witness to recent protests that turned ugly after use of batons, tear gas and rubber bullets against civilians protesting rigged elections in Pakistan, it was interesting to compare various responses on the #IndexDrawtheLine Twitter feed offered by participants from different parts of the world. An article shared by Fiona Bradley during the debate on Twitter discussed attempts made by Chinese authorities to censor use of police force against pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong. The use of tear gas and counter protesters to disperse demonstrators has also changed the popular opinion regarding the city’s police that was once considered to be the best in region. On the other hand, an Amnesty International report revealed cases of excessive use of force by Brazil’s police throughout the protests that erupted before and during the Fifa World Cup this summer. This clearly depicts the extent to which police can be used by local authorites against civilians’ voicing their opinion publicly.

In an interview for the PBS Newshour, Margaret Huang, deputy executive director of campaigns and programs at Amnesty International’s US arm, raised an important point about the tactics deployed by the police in Ferguson, Missouri, during protests during there. “The police’s reaction might have been an overreaction. It may have actually been a violation of international standards for appropriate police response. If your purpose is to disperse people, tear gas is not a great tool for that,” Huang said. “It’s worth noting that tear gas is actually a weapon that’s not allowed to be used in warfare”, she said, “because it can be indiscriminate in who it targets. So the fact that police agencies in [the US] use it for crowd dispersal raises huge concerns about whether that’s a useful or appropriate response.”

Another important concern that has been raised is the increasing militarisation of police that is counter productive and looks more like an intimidating combat against foreign enemies in a war zone. In this case, should protesters have their own force to protect them in case the police start firing rubber bullets and tear gas on non-violent protesters or should there be appropriate training on dealing with such scenarios, keeping in mind the wide difference in domestic and military operations?

It is generally accepted that the state has an obligation to prevent injury and loss of life during public gatherings while maintaining public order to prevent social disruption and damage to property, according to the United Nations. Disgraceful police excesses will continue unabated during public gatherings unless authorities bring police tactics in line with basic human rights standards whether they belong to US, China or developing countries in south Asia and the Middle East.

A few participants from Pakistan offered the point that their country’s police cannot be trained on the lines of “protect and guard” instead of “us versus them” unless officials are appointed on merit without any political interference. But in the case of countries where political interference during recruitment isn’t the problem, one can not help but wonder about the steps required to make the police fall in line with defined international standards.

In the wake of G20 protests in London during the year 2009 that resulted in the death of news vendor Ian Thomilson, the Metropolitan Police came up with a 60 page report Adapt to Protest which advocated the need of major reforms required to deal with policing of protests. The report made a number of immediate recommendations that stressed facilitating peaceful protests, improving communication with the public/ protest groups through dialogue and moderating the impact of containment for proper access of food, water and other essentials. It acknowledged the dire need of giving importance to human rights during operational decisions and training that is needed to equip officers with tactics for effective policing and facilitating of protest activity. Such steps need to be introduced by law enforcement and then implemented independently which is not possible without the cooperation of political authorities and the public.

In this age of instant communication, people are bound to question images and videos of police abuse during mass protests accessible through internet and live television. The only way for police to strike the balance in maintaining peace and protecting civilians’ right to free speech and assembly is to start approaching it as a healthy expression of democracy instead of a menace that needs to be stifled and discouraged.

This article was published on 10 October 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

11 Sep 2014 | Draw the Line, Youth Board

Free expression and policing can have an antagonistic relationship. Recent events in Ferguson are demonstrative of the issues that arise as the demands for protest clash with those for civil safety.

The police are naturally drawn to the forefront of such a debate as they become the physical manifestation of a state’s commitment to free expression and the right to protest. Thus, as the Obama administration launches a federal investigation into whether the Missouri police systematically violated the civil rights of protesters, it is prescient to ask whether one can demand more of the police to protect free expression.

Undoubtedly, enforcement agencies across the world play a tricky role in facilitating expression while protecting the legitimate safety concerns of the local community. Between 2009 and 2013, police in England spent £10 million on security arrangements for EDL marches. There can also be a huge social cost to galvanic protest and the director of Faith Matters, Fiyaz Mughal, has called for a ban on such marches, claiming that “[We] know there is a corrosive impact on communities, it creates tensions and anti-Muslim prejudice in areas. I think enough is enough. I think a banning order is necessary with the EDL”.

What the recent altercations in Ferguson illustrates is that the role of the police in safeguarding free expression must not be overlooked. More importantly, this is a global issue and as six activists being retried for breaching Egypt’s protest law have started an open-ended sit-in and hunger strike it must be remembered that this debate truly gets to the heart of the basic demands of any civic society.

As scenes from Ferguson have at times resembled the images of police crackdowns in Cairo it is clear that complacency about such issues can prove disastrous. It therefore seems vital to drawn certain lines as to where we feel the police should stand when it comes to creating the basis of a safe but also free society.

This article was posted on 11 Sept 2014 at indexoncensorship.org

7 Aug 2014 | Draw the Line, Events, Youth Board

For July’s Draw the Line event, Index hosted a workshop in our offices to debate the question, “Can art or journalism ever be terrorism?” This daunting question provoked some interesting answers, delving deeper into the subject matter the group began to question how do we define art, journalism and terrorism? What do we expect the role of artists or journalists to be in society? And who decides this?

Looking at both sides of the argument we presented the group with several different situations where artists or journalists had been censored and invited them to take part in a role-playing exercise where they had a go at playing both the person being censored and then subsequently the censor.

By playing out these situations from either side of the debate, the group found that it became more and more difficult to say who was definitively right and wrong in each of these situations? Who had the more legitimate right to express themselves? We all agreed the bottom line, of course, should lie in the guarantee of basic human rights for all sides – perhaps as laid out in Article 10 of the Human Rights Act, Article 19 of the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights or America’s First Amendment.

These discussions all finally lad into a formal debate with two teams arguing for and against the statement ”This house believes that art and journalism can be terrorism’.

There was in the end no clear answer, but all of the group came away with many more questions of their own. As one participant said “there’s no black and white answer as I’d previously assumed”. All agreed that a wider debate was needed on the role art and journalism play in society, as well as more information on how that can and does differ all over the world.

Keep up with the debate on Draw the Line here and keep an eye out for our next event where we will be facing a new question and asking where do you draw the line on free speech?

Abishek Phadnis

Abishek Phadnis Ásta Helgadóttir

Ásta Helgadóttir Catarina Demony

Catarina Demony Jordan Mitchell

Jordan Mitchell Kay Robinson

Kay Robinson Mahima Singh

Mahima Singh Mari Shibata

Mari Shibata Mohanad Moetaz ElHawary

Mohanad Moetaz ElHawary