Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

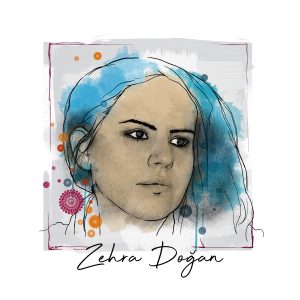

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_video link=”https://youtu.be/HVXGKrAjRnE”][vc_column_text] Released from prison on 24 February 2019, Zehra Doğan is a Kurdish painter and journalist who, during her imprisonment, was denied access to materials for her work. She painted with dyes made from crushed fruit and herbs, even blood, and used newspapers and milk cartons as canvases.

Released from prison on 24 February 2019, Zehra Doğan is a Kurdish painter and journalist who, during her imprisonment, was denied access to materials for her work. She painted with dyes made from crushed fruit and herbs, even blood, and used newspapers and milk cartons as canvases.

Doğan used to work in Nusaybin, a Kurdish town caught in the crossfire between Turkey and Kurdish militants. She moved to the town to report on the conflict in 2016 and edited Jinha, a feminist women-only Kurdish news agency reporting in the Kurdish language.

When she realised her reports were being ignored by mainstream media, Dogan began painting the destruction in Nusaybin and sharing it on social media, and her art became important evidence of the violence in the town.

Doğan focused on striking, dark political scenes, but also on colourful scenes of traditional Kurdish life. In her most famous artwork, she adapted a Turkish army photograph of the destruction of Nusaybin, depicting armoured vehicles devouring civilians. In July 2016, she was arrested where witnesses testified in court that she was a member of an illegal organisation.

Although her trial ended with no sentencing, Doğan remained in prison until December 2016. In March 2017, Doğan was acquitted of “illegal organisation membership” but sentenced to almost three years for “propaganda” – essentially posting her painting on social media.

Her persecution is not isolated and takes place amid a crackdown on Turkish civil society. Using emergency powers and vague anti-terrorism laws, the authorities have suspended or dismissed more than 110,000 people from public sector positions and arrested more than 60,000 people between the attempted coup of July 2016 and the end of the same year.

Together with media and academic freedom, artistic freedom has come under attack. As a result, according to the Economist: “Artists have become more cautious, as have galleries and collectors.” Doğan’s situation was noticed by many artists in the world: Banksy painted a huge mural for her in New York and Ai Wei Wei sent a letter to her.

During her time in prison Doğan continued to produce journalism and art. She collected and wrote stories about female political prisoners, reported human rights abuses, and painted despite the prison administration’s refusal to supply her with art materials.

Doğan produced her own paint from food, drinks, and even her menstrual blood. She did not have brushes but used feathers of birds that fell into the prison yard. Security guards seized and destroyed the paintings she tried to send out of prison and punished her with a ban on communications with the outside world. She also gave drawing classes to other inmates and taught them how to make their own paintbrushes.[/vc_column_text][vc_separator][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_single_image image=”104691″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2019/01/awards-2019/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/2″][vc_column_text]

Index on Censorship’s Freedom of Expression Awards exist to celebrate individuals or groups who have had a significant impact fighting censorship anywhere in the world.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][vc_separator][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1551975581366-1308b39d-3e20-6″ taxonomies=”26925″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Artist Zehra Doğan, a Kurdish painter and journalist, has been released from a Turkish prison. Dogan, originally sentenced to two years, 9 months and 22 days on 24 March 2017, was tried over a painting depicting the destruction in the town of Nusaybin and sharing it on social media which was deemed by the courts as “terrorist propaganda”.

While in prison, Doğan, who has been nominated for a 2019 Freedom of Expression Awards in Arts, continued to write and produce art despite not having access to materials. The artist began using food and even her own blood as paint and letters, milk cartons or newspapers as her canvas. Doğan had also founded JINHA, Turkey’s first women’s news agency, which was shut down in 2016 under Statutory Decree No. 675 along with 180 other media outlets in the wake of the failed coup.

“We are very pleased to hear about her release and that she can rejoin her loved ones,” says CEO of Index on Censorship, Jodie Ginsberg. “We admire her strength and her perseverance to keep her art alive despite imprisonment and conditions. Her detention was unjust and we hope that there is justice for her and many others who continue to be arbitrarily detained in Turkey.” [/vc_column_text][vc_row_inner][vc_column_inner width=”1/4″][vc_single_image image=”104529″ img_size=”full” onclick=”custom_link” link=”https://www.indexoncensorship.org/2019/01/awards-2019/”][/vc_column_inner][vc_column_inner width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

Zehra Doğan, a Kurdish painter and journalist, has been shortlisted in the Arts category for the Index Awards 2019. Find out more.[/vc_column_text][/vc_column_inner][/vc_row_inner][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1551005624780-09a05fdd-dde0-1″ taxonomies=”55″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]

Kurdish artist and journalist Zehra Doğan

The last time Onur Erem and his girlfriend Zehra Doğan, a Turkish artist and journalist, met face-to-face, she was chirpy and seemed happy, he recalls. They sat at a picnic table and talked about her art being concurrently exhibited in various places around the world, from New York to Europe. They were surrounded by other families, busily conversing amongst each other at the picnic tables to their left and right.

But this was no picnic. Two prison guards walking up and down the aisle in between two rows of tables screwed to the concrete floor, eyeing the prisoners and their families with forced indifference masking wariness, made sure no one lost sight of the fact.

“She was in good spirits,” Erem says, attributing it to her continuing to create art while in prison, just like she did on the outside, before her sudden arrest as she was awaiting the outcome of the court case against her on charges of spreading propaganda in favour of a terrorist organisation.

“She writes down the stories of the people she met there. Since there’s not much in terms of the supplies on the inside, she uses the dyes that she makes from food. They don’t give her canvass, so she draws either on clothing or envelopes from the letters she receives. She collects the bird feathers that fall in the prison yard and makes improvised brushes out of them,” he explains.

The reason for Doğan’s incarceration was the drawing she made while covering the Turkish military operation in the town of Nusaybin on the border with Syria, populated mainly by Kurds. The drawing was made based on the photograph that had previously been circulated widely by the Turkish military on social media, according to press reports and Erem. The point of contention is whether the original photograph did or did not include the flags of the Turkish Republic hanging from buildings half-destroyed during the operation.

“She drew a military vehicle in the form of a scorpion. I’d say, this was her only addition to the photograph itself,” he says explaining that the military vehicle his girlfriend depicted in such a manner is referred to as “Akrep”, the Turkish word for a scorpion. “However the judge, in spite of all the evidence presented, sided with the opinion that the photo was taken by Zehra herself, that the original photo didn’t contain the Turkish flags hanging from the destroyed buildings and that [she] added them on for propaganda purposes, and thus, by way of this picture she was engaged in a propaganda on behalf of a terrorist organisation.”

Boxing the art

The widely-shared narrative is that Erdogan lashed out against artists after the July 2016 coup attempt. However, his government had gone after scores of artists and their freedom of artistic expression much earlier, of which Doğan is but one example. Two years after the coup, the crackdown doesn’t seem to dissipate, and the arrest of Turkish rapper Ezhel on inciting drug use in his songs on 24 May 2018 being the latest occurrence.

Attacks on artists across Turkey range from firing of one of the country’s most prominent orchestra conductors İbrahim Yazıcı for his criticism of the Erdogan government, to decapitating Ankara University’s theater department by dismissing Tülin Sağlam, its head and five other senior professors critical of the authoritarianism; from arrests of popular cartoonists, such as Cumhuriyet newspaper’s Musa Kart, to handing down a 10-months sentence against Zuhal Olcay, one of the country’s most popular singers and actresses.

The limitation of artistic freedoms is clearly a trend in Turkey, says Julie Trebault, Director of Artists at Risk Connection, an artistic freedom non-profit based in New York, adding that while in the past two years the attacks have escalated, they’d started before the coup attempt.

Years in the making

“We have several cases, for example, the case of the two filmmakers who have released their film, Bakur in 2015. Bakur was screened at many festivals in Europe for a couple of months without being censored or attacked. And then, in 2015, at the 34th Istanbul film festival, just hours before the premiere, the film got censored,” she recalls, explaining that the film was a documentary about the PKK, a Kurdistan Workers’ Party that is considered a terrorist organisation by the government of Turkey.

As to the persecution of artists even before the coup, Trebault adds “When Erdogan became president, things went down and down and down in Turkey. It took years to arrive where we are in Turkey [now]”.

Turkish filmmaker Elif Refiğ sees the roots and the reasons for the persecution of artists in the Gezi Park protests of 2013. “There had been a very serious oppositional sentiment that had collected in the society until then, that failed to organise until that moment. A very important feature, it included artistic institutions, and its nature was very creative to the extent that it changed the very definition of ‘disobedience’,” she says. According to her, it was a completely peaceful campaign spearheaded by arts institutions that didn’t tolerate violence, and it spread all over the country.

Refiğ points out that in addition to arrests, torture and jailings as ways for the state to punish the disobedient artists that often meet the eye, there are other ways of applying pressure: “The economic obstacles make the lives of the artists miserable. Blacklisting. It makes it difficult for the people to find work, impedes their freedom of movement.” As the case in point, she cites Füsun Demirel, popular television and cinema actress who has been struggling to find work for the past three years because “she is a Kurd, and because she openly voiced her opinions.”

As harmful as it is for the arts in Turkey, the crackdown on the freedom of artistic expression has also affected the general public, Trebault says.

“There’s definitely more self-censorship. People tend to get less out about those issues. People tend to be extremely careful on what they are saying,” she adds.

Responding to a question about the public’s reaction, Refiğ says that, although, the general public is critical, “Where would the criticism from the society be coming from? At this point, all television channels, all newspapers have been silenced by the forces in power.” She explains that multiple ongoing court cases against the media outlets are having a chilling effect on the public.

While the Turkish society is succumbing to self-censorship and its artists are fighting to get out their artistic word amid incarceration and repressions, the international community is struggling with possible solutions.

International support coming too late

“In my personal opinion, the international support is coming to Turkey too late,” says Refiğ. She explains that some international institutions like Pen America or Amnesty International are doing their best to call the international attention to the ongoing crisis with the freedom of expression in Turkey, while others, “institutionalised international organisations,” as she terms them, such as the E.U. and the Council of Europe, for instance, have their own pressing concerns-not letting the mass influx of refugees from the conflicts in the MENA region to cross into their borders, and, therefore, desperately needing the co-operation of the Turkish government.

“At very critical points, when they shouldn’t have restrained their words, they stood by our government, as they were afraid of the opening of the borders [by Turkey] and a free movement of Iraqi and Syrian refugees to Europe” she says of the international institutions. “Hypocrisy is the word that even might come to one’s mind. Words-wise, there’s a lip service to improving the human rights situation in Turkey, but action-wise, there’s very little acting upon it, unfortunately.”

Trebault, on the other hand, says Turkey, as a member of various international bodies is a signatory to important international human rights treaties, and Western governments should call on its government to abide by them.

Grim prospects, great expectations

Looking into the future, Trebault says she doubts things will get better in the next few years in Turkey.

“In 2017 the referendum gave even more power to the president,” she says of the plebiscite that effectively abolished the parliamentary system existing at the time and replaced it with the presidential system with a much stronger executive. “So, to be honest with you, I don’t think there will be changes for the better with this government,” she says.

Back in Diyarbakır’s E-type maximum security prison, while counting days until her release, Doğan is also pondering her future.

Making plans for after her release upon completing her two-and-a-half-year sentence next February, Erem says Doğan plans to continue working on her art, as well as her work as a journalist. “Currently, there’s an exhibit of her artwork In France that includes paintings and drawings smuggled out of the prison, as well as her previous work. This draws the attention of the artistic community, as well as the society at large, that’s why she wants to continue.”

He says that his girlfriend is also taking notes while in prison that she’s planning to use for writing a book when she is out.

“Of course, the solidarity that she sees on the outside also helps a lot. [It] helps her and her jailed friends to keep their spirits high, as they see that their voices are heard on the outside and there are quite a few people who don’t want to leave their side.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1528275200044-7774f8c3-7f31-3″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_media_grid grid_id=”vc_gid:1520507629250-860b1635-f01a-8″ include=”98413,98412,98411,98410,98409,98408″][vc_column_text]The only online feminist news website in Turkey is marking International Women’s Day under state censorship. Access to the website of Diyarbakır-based Jin News (“Jin” meaning “woman” in Kurdish), which is entirely run by women and specifically focuses on news relating to women, was blocked seven times within just one week at the end of January. At present, the site is inaccessible from Turkey.

The pressure, however, hasn’t discouraged Jin News’ journalists. “We have always shown that we have alternatives, and we are continuing to show it,” Jin News Editor Beritan Elyakut told Index on Censorship. While relying on social media and the use of VPNs, Jin News announced a new TV channel to mark the symbolic day, which has a double significance for them. JINHA, the first news agency run by women in the entire country, was also established on an International Women’s Day six years ago.

Pressure was no stranger to them either: They were shut down not once but twice, more than any other news outlet in the country under the present state of emergency. First, JINHA was closed by decree in October 2016. Gazete Şujin, JINHA’s successor, was only allowed to exist for nine months before another decree ordered its closure in August 2017.

But still, from its ashes, Jin News was born, taking over JINHA’s legacy: a style of news writing that presents women “as subjects, not objects.” The site takes care to use conscientious language, such as using the word “murdered” instead of “killed” to emphasise male violence. They also avoid highlighting details that indirectly justify violence against women (by refusing, for example, to note that she was seeking a divorce) or providing unnecessary descriptive details in cases of sexual attack. Then there is the strict use of first names instead of family names – a practice adopted by the present article to provide a glimpse of their methodology.

“When covering women, we had to think until the smallest details. We chose not to employ the family name to break the perception that family lineage descended from men. If we say ‘Beritan Elyakut’ in the beginning of the article to introduce a person, we then use the name distinguishing that person as a subject,” Beritan said. Even the highest-ranking officials, including two former co-chairs of the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) who are currently under arrest, Figen Yüksekdağ and Selahattin Demirtaş, wouldn’t escape the rule.

This also meant a different approach in the choice of topics. “We don’t just cover news on sexual attack, sexual abuse or harassment. We started to cover stories reflecting women as strong individuals. We reported on pioneering women. We focused on economy and ecology. We made women visible in politics, highlighted them and gave them a voice,” Beritan said. [/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column width=”1/4″][vc_icon icon_fontawesome=”fa fa-times” color=”black” background_style=”rounded” size=”xl” align=”right”][/vc_column][vc_column width=”3/4″][vc_column_text]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Encouraging women to speak up

To ensure that women’s voices are not muted, Jin News uses exclusive testimonies and quotes from women in their reports. As she walks to the popular market of Bağlar in Diyarbakır, reporter Şehriban Aslan tells Index on Censorship that women’s reactions are always very positive when they introduce themselves as a Kurdish agency covering women.

Once she arrives at the market, Şehriban and her colleague, Rengin Azizoğlu, walk quietly as they search for women running stores. The subject is the destruction of a community health centre, which was turned into a police station by a government-appointed trustee after the municipality’s democratically elected co-mayors were thrown in jail.

The effect is immediate as they enter a gift shop. One of the vendors agrees to be interviewed. “There is this perception in society that a woman can’t work. You’ve broken it,” Şehriban tells her. “Absolutely,” the woman answers, without a flinch of hesitation. As the interview nears its end, Şehriban asks her if she has any messages to other women. “Women should absolutely work,” she says. “They shouldn’t submit to men.”

“Women feel comfortable and confident when they speak to us,” Şehriban says. “Being a Kurdish agency also helps.”

“Which outlet are you from?” a man asks her as she sneaks out of a shop. “We are the free media,” Şehriban says, using the expression that Kurds refer to their own media outlets. “Ah, you are more than welcome,” he replies.

Münevver Karademir, Jin News’ Kurdish-language editor, also stresses the importance of the encouragement factor. “When you give them confidence to express themselves, women embrace you,” Münevver says. “When you tell any shop vendor ‘I am an agency run by woman who works on the problems of women,’ her attitude becomes very different. She feels safe. She is able to tell you what she is going through.”

Jin News journalists are also eager to expand the know-how they are building with other outlets, especially male journalists. They have a project to prepare a dictionary on non-discriminatory news language. “We were planning to come together with men and organize training on ‘how to design a news story’ and ‘how to use women-friendly language in news articles’ but haven’t been able to due to the conditions [in the region],” Beritan says.

However, their mere presence has already started to raise some awareness. “Some journalists, men most of the time, ask us: ‘Would you check this story and see if we have used correct language?’ They now feel that concern,” she says. One of the most important successes for Beritan has been to show that women were more than capable of doing journalism – often better than men. “We saw that women were fast as well. But their speed also seeks to share a story in the best way possible. They were meticulous.”

Women journalist establish platform against pressure

According to Beritan, Jin News’ policy of collecting women’s voices alone was more successful in the east than the west of Turkey. This is the result of the strict “co-chair parity” policy launched by the HDP, which ensured that women assumed senior positions in Kurdish municipalities. However, after trustees occupied most HDP-led municipalities, Jin News not only lost its interlocutors – most trustees are men – but lost an important source of revenue. Indeed, many women co-chairs ensured that the municipality subscribed to their services and encouraged the agency’s activities.

Since the military crackdowns in urban centers in the region, journalists have become a target of state security agencies, and arrests and detentions have become common practices.

“The state wanted to seclude us at home through detentions. When that didn’t work, they tried to shut down the outlets entirely,” Beritan says as she learns that one of their reporters, Durket Süren, has been charged with “membership in and financing of a terrorist organisation” after being detained a few days earlier at a routine checkpoint. Durket was eventually released by a court but was subjected to a travel ban and ordered to sign in regularly at a police station.

Durket is hardly the only Jin News journalist facing criminal charges. Former JINHA reporter Zehra Doğan is currently serving a two-year, nine-month prison sentence for “spreading propaganda for a terrorist organisation.” She was convicted for publishing the testimony of a 10-year-old girl affected by the Turkish military operation on the town of Nusaybin in an article from December 2015. Also a painter, Zehra received jail time for “drawing Turkish flags on destroyed buildings” in a painting copied from a real photograph in which Turkish flags can be seen on buildings destroyed by Turkish forces. Beritan Canözer, the agency’s Istanbul reporter, and Aysel Işık have also served prison sentences. Many have been detained, and about 10 reporters are currently on trial. The agency also receives regular threats.

Ayşe Güney, a reporter for the Kurdish Mezopotamya Agency and spokeswoman for the Mezopotamya Women Journalists Platform, told Index on Censorship that state violence has become routine practice. “In a province like Şırnak, our reporters are constantly subjected to verbal harassment or threats. Many avoid going alone to villages or certain neighbourhoods. They are threatened, from being kidnapped to being abused or raped. Threats may be verbal for now, but there is a serious attempt to intimidate them,” she says.

The platform was established in 2017 on another symbolic day, May 3 Press Freedom Day, to ensure that women can fight together against common issues. Those include social issues – such as unemployment after the repeated closure of Diyarbakır-based Kurdish media outlets – but also against all kinds of violence. “Thanks to this association, we wanted to help our friends who are detained, arrested or subject to harassment from sources, attacked or abused by the police. We also wanted to make the pressure visible,” Ayşe says.

The latest woman journalist to be arrested by police is Seda Taşkın, who was reporting a story in the province of Muş. Seda was first released on probationary conditions, only to be arrested a month later in Ankara due to her reporting and tweets.

According to Ayşe, it is no coincidence that the women’s journalistic experiment began in Diyarbakır and not – as some might have expected – in Istanbul. “Our people know how to live under difficult situations. Kurdish women know how to resist. JINHA was closed, and Şujin was created. Şujin was closed and Jin News was created, which means we can reinvent ourselves over and over,” Ayşe says. “We are speaking here about women’s freedom and not gender equality. This is something that goes way beyond it.”

Ayşe also said she wished to make a call on all women journalists in Turkey to engage in solidarity. “There are almost no journalists here who haven’t had a trial opened against them. Either they have been in and out of prison or have to report at a police station every two or three or even five days. This means they can’t leave the city, which is becoming an open-air prison,” Ayşe says. “But it doesn’t happen only to Kurds anymore. It happens everywhere. So this is the time to act together.”[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row][vc_row][vc_column][vc_basic_grid post_type=”post” max_items=”12″ style=”load-more” items_per_page=”4″ element_width=”6″ grid_id=”vc_gid:1520507629256-32297f2b-810d-7″ taxonomies=”8607″][/vc_column][/vc_row]