Index relies entirely on the support of donors and readers to do its work.

Help us keep amplifying censored voices today.

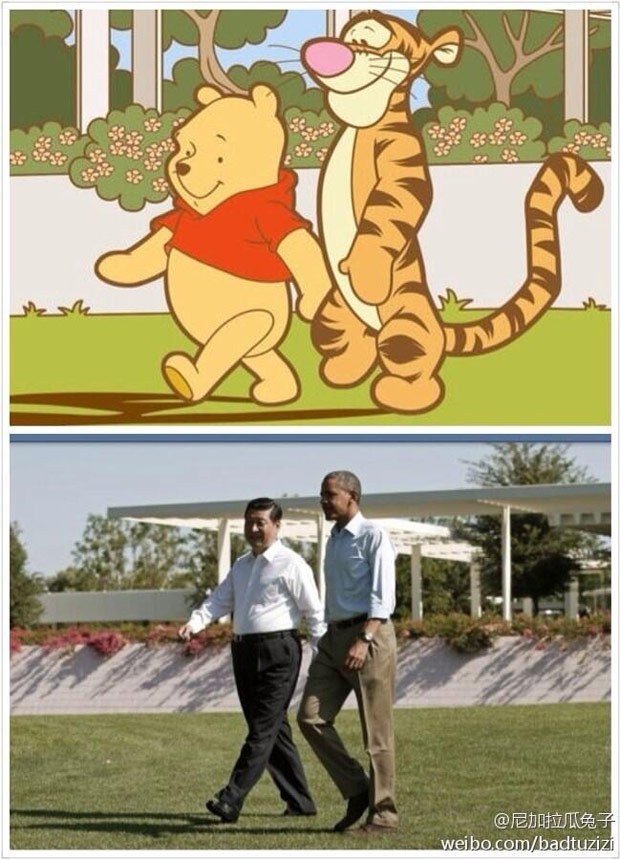

China has censored an image of Winnie the Pooh strolling with Tigger, after it went viral on popular Chinese microblogging site, Sina Weibo.

China has censored an image of Winnie the Pooh strolling with Tigger, after it went viral on popular Chinese microblogging site, Sina Weibo.

The image was circulated after bloggers noticed the similarities between a photo snapped this week of President Barack Obama and Chinese premier Xi Jinping and an illustration of the cartoon characters.

China’s censors are known for their lack of a sense of humour: earlier this month, censors deleted a photoshopped version of a famous picture showing a single protester standing before a row of tanks in Tiananmen Square, where the tanks were replaced with large rubber ducks.

Sara Yasin is an Editorial Assistant at Index. She tweets from @missyasin

On the 24th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square protests — when Chinese security forces carried out a violent crackdown on protesters occupying the legendary square in Beijing’s centre killing hundreds — Index on Censorship calls on the Chinese government to honour its constitutional commitment to free speech and to allow free access to information about the events. Sara Yasin writes

China has been working hard to crush attempts to commemorate the anniversary — both on and offline. Dozens of police officers have blocked the gates to the Wanan cemetery where victims of the massacres are buried, visited annually by the Tiananmen Mothers.

China has been working hard to crush attempts to commemorate the anniversary — both on and offline. Dozens of police officers have blocked the gates to the Wanan cemetery where victims of the massacres are buried, visited annually by the Tiananmen Mothers.

China has declared today “Internet maintenance day” — where the authorities darken sites in the name of “maintenance.” In previous years, China’s day of online maintenance has included shutting down blogs and websites with reputations for veering from the ruling party’s line. The Chinese-language Wikipedia page containing an uncensored account of the massacre was blocked by authorities on Monday.

Users of China’s most popular microblogging site, Sina Weibo, have been blocked from typing in variants of phrases like “June 4”, “Today”, “candle”, and “in memory of.” Also included in the banned list is “big yellow duck” — a reference to a photoshopped image where tanks were replaced with rubber ducks in the iconic photograph of a lone protester standing before a row of tanks in Tiananmen Square.

The United States today called on Chinese authorities to release the full account of those two bloody days, as there is not even an official death toll. China shot back through the state-run Xinhua news agency, urging the US to “stop interfering in China’s internal affairs so as not to sabotage China-US relations.”

A reputation for censorship

China’s ruling Communist Party has also recently released a list of seven banned topics, and has been quick to curb discussion of the “dangerous Western influences” online. The political topics, which include “freedom of speech”, “civil rights”, “crony capitalism”, and “The historical errors of the Chinese Communist Party”, were banned by the country’s top propaganda officials. When East China University of Political Science and Law professor Zhang Xuezhong posted the seven “speak-nots” online, the post was quickly deleted by censors.

As Wen Yunchao wrote for Index, Chinese censorship is “mainly aimed at the control of news and discussion of current affairs. Day-to-day censorship in China falls into two categories. The government’s propaganda authorities supervise websites that are legally licensed to carry news, while those without a license are dealt with by the public security authorities and the internet police. Unlicensed websites that are considered particularly influential may also be overseen by propaganda officials.”

The Chinese state’s control of the web is a model of bad behaviour for other nations around the world, according to a New York Times report. A dirty dozen or so control what the country’s citizens read and write online.

With over 500 million web users in China, the shear size of the Chinese user base makes censorship a leaky bucket for the country. A study conducted by two American computer scientists estimated that 30 per cent of banned posts are removed within half an hour of posting, and 90 per cent within 24 hours. Suzanne Nossel, executive director of the PEN American centre, wrote in April that China’s censors are caught in “a race against new platforms and technologies.”

The country’s notoriously strict censorship machine has earned it low rankings for press freedom and freedom of expression: it ranked 173rd out of 179 in this year’s World Press Freedom Index released by Reporters Without Borders — only coming ahead of free speech all-stars Iran, Somalia, Syria, Turkmenistan, North Korea, and Eritrea. According to the report, “commercial news outlets and foreign media are still censored regularly.” The Committee to Protect Journalists has reported that China uses libel suits to silence journalists — and there are 32 jailed journalists as of December 2012.

Chinese censors have been working overtime on social network Weibo after users noticed that the new headquarters of state propaganda sheet the People’s Daily News (see pic) looked, er, a bit phallic.

According to the South China Morning Morning Post, Weibo searches for “People’s Daily” and “building” appear to show that the terms have been blocked.

“It seems the People’s Daily is going to rise up, there’s hope for the Chinese dream,” quipped one Weibo user.

Padraig Reidy is senior writer for Index on Censorship. @mePadraigReidy

Chinese censors have been working overtime on social network Weibo after users noticed that the new headquarters of state propaganda sheet the People’s Daily News (see pic) looked, er, a bit phallic.

According to the South China Morning Morning Post, Weibo searches for “People’s Daily” and “building” appear to show that the terms have been blocked.

“It seems the People’s Daily is going to rise up, there’s hope for the Chinese dream,” quipped one Weibo user.

Padraig Reidy is senior writer for Index on Censorship. @mePadraigReidy